It's guest writer time, all words from the ever wordy Tin Dog, only the names have been changed to protect the innocent....

As

promised to nobody, here is the whole story of our trip to Ukraine. I

travelled with two intrepid chaps, Urban Spaceman and Fragglehunter, both of whom are old enough to

know better; taking in Kiev and the nuclear exclusion zone containing the Chernobyl

reactors and the ‘ghost city’ Pripyat.

The

Soviets lied when it happened, they've lied to us during the intervening years

and Ukraine

is still lying to the world now. However much they attempted to put a positive

spin on the ongoing work, Chernobyl

is a radioactive mess that will still be a problem in twenty thousand years. It

will never go away.

Ukraine from above was very unusual. There was

no landscape. I have flown over many countries and they all have hills,

mountains, valleys, lakes, forests, cities, and land of varying hues. Not Ukraine. Ukraine is flat

and white for hundreds of miles in all directions. White and flat forever. This

is a country that is so flat that, with binoculars, you could watch your dog

run away in the snow for three days - run Fido run!

Kiev airport was very modern except it had

no shops, cafes or any other amenity. Staffed by Soviet era looking guards in olive

green fatigues, guns and stares cold, Ukraine announced itself and it was

glum.

We left the building to seek the smoking

area. It was in a windy bus shelter at the end of the platform and therefore

never needed sweeping. Nothing could stay or live there for long.

Our contact began like this;

We were met by a very square shaped man,

in a black VW van...eventually. He was looking for us whilst

being pursued by the police for a parking infringement in the

airport. He could not park up to meet us for more than a minute before

the Ukrainian boys in blue arrived. The police turned out to be very

scary people and best not encountered. His reticence in pulling up for any

length of time was understandable.

We phoned our contact in Kiev who assured us our

driver was in the airport looking for us. As we wandered a car park looking for

said van, we heard shouty beckoning in Ukrainian from the square shaped man. He

was across two busy car lanes outside the airport entrance, with the police

crawling towards him - the police were staring at us three chumps.

We ran through moving traffic with our

luggage to get to our van before the police could arrest our man. Bags chucked

in and doors slammed, we took off at high speed into a dual carriage way

that led to Kiev

proper. It wasn’t a car chase, more of a brooding, malevolent tail-gating. The

police gave up or got bored as we left the airport perimeter.

Welcome to the gangster run kleptocracy

that is the State of Ukraine (and just look at the bloody state of it). The

news is State controlled and the police aren’t.

Our driver spoke not a word all the way

to our digs, forty minutes away.

The language chasm took care of that.

Incongruously, Lennon’s ‘Imagine’ seeped from the van’s speakers.

When we arrived at our digs in the city

the fun began. We had insisted that we would be stopping together. Not in the

same room of course, ahem, but in adjoining rooms.

Kiev Digs

We arrived at what can only be described

as a hippy commune in an old Soviet block, in the centre of town. Then we were

informed that there was 'no room at the inn' for two of us. We would be

stopping at separate locations nearby. Kiev

is a place that it's best to have the security of friends with you. Urban Spaceman and I

were led off into the bitterly cold night to digs in different locations. Fraggle,

being the man who started this whole crazy business, got first dibs. He

consequently spent the night on a thin mattress on the floor of a box room office,

with fairy lights flashing pretty colours on and off all night. How the Spaceman and I

laughed when told the morning after, by a very pissed off Fraggle.

The entrance to the place I stopped in

was not inviting. Two grey, heavy plate steel security doors were entered by

security code. The graffiti across them didn't add any stars for a web review.

Inside was akin to a cross between a backpackers and Soviet utility,

over-engineering.

The radiator in my room could’ve kick

started the whole global warming thing, single-handedly. I was only doing two

nights there, Thursday and the Saturday after Chernobyl and Pripyat. The digs were like

being eighteen again but with all the fun bits removed. It was the least of my

worries, considering where we were headed. We were all very thirsty by

now. We needed drinks, food and plans.

Morning Meet

Miraculously, we managed without wives

or alarms, to meet at the agreed place at seven forty-five...the morning after

a large night out in a twenty four hour cellar bar; where vodka was as cheap as

it should be and steak dinners cost wads of Ukraine money (£1.50).

We met at a bus stop that none of

us had ever seen beyond a street map. We were all competent idiots, there at

the appointed hour. It was fiercely cold. I had kitted out with so

many layers, be-scarved and topped with black woolly hat that yes, I did

look like a fat, armed robber. We took a bus to the central train station, the

tour meeting point.

Kiev train station inside is very ornate.

This information does not help this tale in any way and is quite useless.

Kiev station at morning rush hour needs to

be seen to be believed. It was severely cold. A brutal, biting wind swept the

station entrance. Kebab stalls were selling morning kebabs which consisted of

rancid, fatty meat on a roll as thick as an off-road car tyre. It was grey

where it wasn’t a sceptic yellow. It would be safer eating car tyres.

The evil yellow M

of McDonald's was doing a roaring trade. Obviously most of the profit

goes to Mac's headquarters in the US. This being a kleptocracy, they

had a way around this. They have built an identical building with identical

coloured livery, just next door. It sells ersatz Mac' meals that undercut their

rivals and it sells beer, at breakfast time. Its name in Mac’ style lettering

and colouring, I kid you not, is McFoxy's. Meanwhile, ruddy-faced commuters

rushed to mystery destinations in heavy overcoats and bubble coats and fur

hats, whilst shouting into mobile 'phones. Beggars began to mither for money

and moved on when stall holders harangued them. To English ears, Ukrainian

sounds aggressive, like the beginning of a fight, especially when being shouted

at the freezing beggars.

We met a man with a sign proclaiming, 'Chernobyl and Pripyat tour - see, feel,

experience...but don't touch!' We

had our man.

Another mini-van, another hundred kilometres,

to the nuclear exclusion zone.

Exclusion Zone

Once out of the city we were driven through

the flat, featureless landscape. This was a two hour drive through the country

glimpsed from the 'plane. The road to Chernobyl

stretched out, miles straight, into the distance.

Stood in the centre of the road, looking

down the dotted white line, it was framed into a funnel by bare trees on either

side to the horizon.

Either side - frozen wastes of nothing.

Occasionally, the road margin of trees

fell away to reveal, within clear view, wild horses grazing in small herds. On

the other side were machines - bulldozers, cranes, trucks and other heavy,

rusting transport. We pulled over for a break and the introduction to our

official guide.

A woman in her late twenties wrapped

against the severity of a Ukraine

winter, she was smiling and friendly and a little nervous. Our small group

stood smoking and chatting. In one’s and two’s people peeled away to take the

first of several million photo’s.

A huge wooden crucifix had been planted

nearby; a traditional Ukrainian women's head-scarf, white with a blood red-rose

pattern wrapped around it. We began to realise the gravity of the whole trip. I

can't say I wasn't worried, I was. We all were. It was apparent that whatever

we'd researched and prepared for, it would be lacking. We had to pass

three checkpoints to reach our hotel nearly thirty miles away, a mile or so

from the reactors. “Guys, you must not take photo of checkpoint or soldiers.

You will be arrested. Please, take this very serious. It is not joke. It is

dangerous. You must follow advice.” She spoke the English of that irritating

meerkat on that bloody insurance ad, or a Bond love interest in the seventies

movies. Your age will supply you with the necessary reference.

Checkpoint

The nuclear exclusion zone begins thirty

miles from the reactor. We stopped at the first checkpoint and it all got very

serious. You need official, government permission to enter the exclusion zone.

It's not an easy place to walk into. The check point was all your Cold War

nightmares come true. A brick hut next to the road, just big enough to drink

coffee and regret your existence in. Expressionless soldiers stood in olive

camouflage, in three foot deep snow...with shiny, black guns.

I'd been signed up to this tour at the

last minute, back in Blighty. Consequently, I was not with the 'S' names. I was

at the end of the list that the bored guard had been issued with. At gun point,

I showed him my passport. He stared me in the eye then looked down at the

passport. He ran his finger down his list to the 'S' names. His interest perked

up no end. He looked back up at me and I knew there was a problem because in a

heavy accent he said, "There is problem." I was spluttering

explanations when the other soldier pointed his gun at my chest. I raised my

arms in a pathetic 'I'm not armed and I come in peace' show of fear.

All my border guard experiences were

concentrated into that one moment. Gun pointer's friends stepped forward to

surround me and back him up. I insisted that I was on 'the list'.

‘On the list’ sounds very bad if you

consider your history lessons.

“I will put you on ze list! Vat iss your

name?”

“Don’t tell him, Pike!”

‘On the list’ is never where you want to

be at nuclear exclusion zone checkpoints, until now. I was motor mouthing to

justify my presence there when Urban Spaceman sussed the problem. "He's at the end of

the list, not in the 'S' names." Translations were made and they dropped

their guns. I farted quietly, by way of appreciation.

The twenty mile border check was the

same but much less interesting. It was fart free. Climb out of the mini-bus and

produce your documents. Passports and checklists, no problem. No soldiers

threatened to shoot me. Result.

The ten mile check point was stringent

and excitement free. Just pointed guns and passports, again. We were

told that inside this ten mile zone the rules were very strictly enforced. The

rules can be distilled into one phrase, ‘do as you are told’.

One of the rules was no alcohol inside

the ten mile zone. The groan of disapproval and desperation in the bus was very

loud. “Shit! We should have stocked up in Kiev.” was exclaimed in a minimum of

five languages. Then we drove straight to the hotel sulking in those languages.

We were unaware that the drinking ban, unlike other rules, was not strictly

enforced. Then again, we were unaware of a lot of things.

Chernobyl Hotel

The two

star hotel consisted of a two hundred yard long corrugated iron hut with

car park for twenty cars, ringed by a linked wire fence. It looked like a down

beat industrial estate. It was surrounded by identikit concrete flats on one

side, emptiness on the other.

The two

stars were won on the grounds that it had two floors and a roof and, if you

don’t leave the building at night, you will not get shot by a drunken soldier. Really,

we were warned. What more could one need?

A good, firmly earned couple of hotel

hospitality stars there then.

After much queuing Spaceman, Fraggle and I

secured a suite on the upper floor of the hut. Consisting of two main rooms,

toilet and shower room, we’d hit comedy gold. I commandeered a bed in the room

with two beds. Fraggle arrived next to claim the other. Urban Spacman arrived and looked pleased

at the sofa bed in the other room with the TV. A room to himself and very cosy.

When inspected the sofa-bed was covered

in an operating sheet with an operation hole a foot wide sewn into it at the

centre. It was a colour charitably named ‘off white’. Then Fraggle, ever

observant, pointed out the shit splash stain, on the ceiling. Urban Spaceman, eagerly

attempting to play it down, insisted it was only dried blood. That’s okay then, Urban Spaceman. No worries there then. To add to the ambience someone had kindly unplugged

the fridge to enable the bacteria and mould to get a foot hold in the fridge.

We dumped our stuff, gladly free of the

baggage hassle.

The Chernobyl Hilton was not on the list

of concerns. The baggage of the name ‘Chernobyl’

was and is enough.

Three storey blocks of grey, concrete

flats surrounded us into the streets around the main strip. Squat, square and

pock-marked with illuminated windows, these flats house four thousand temporary

workers.

Nobody can be here permanently. It is a

grim landscape of concrete; visited by deep, winter snow and stifling, mosquito

plagued summers. Radiation levels are too high to linger long. This level of

radiation is too high to live in safely. It is cumulative - don’t hang around

too long.

All workers are employed by the

government. Soldiers man the exclusion zone check points and go on to patrol

the zone borders. Others keep the zone working. A small town of constantly

revolving workers exists in this toxic place. They arrive and leave; a constant

movement to attempt to keep them within ‘safe limits’. Three days on, four days

off - they have high paid jobs in the danger zone.

The Tour – Day One

Back on the bus, we made our way to our

first landmark, the monument to the fire fighters and liquidators of Chernobyl. In Soviet

concrete, it depicts the fire fighters sent in within minutes of the explosion.

They entered the wreckage without any knowledge or protection. Without their

blind bravery things could have spiralled into…who knows’?

They died within days. The plaque on the

centre of the memorial, our guide told us, reads, ‘The Men Who Saved The

World.’ If it doesn’t, it should. Without them you may not be reading this. A

chain reaction between these four live reactors does not bare imagination. One

poisoned Europe. What would four do?

After the nuclear explosion, within

hours, helicopters had been despatched to drop lead, dolomite and sand onto the

site, in an attempt to seal it. It had gone way beyond this futile measure. Owing

to the heat, the lead, dolomite and sand melted into the exploded reactor. The

world was in uncharted, nuclear disaster territory. The explosion and

subsequent fire began to burrow into the Earth. There was no plan. The people

of Pripyat were not told what had happened. The authorities wanted to avoid

panic and the attempted cover up began.

The explosion was many times greater

than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

It was contained in the reactor shell. It still ‘blew the bloody roof off’. The

two thousand ton lid of the reactor was blown up through the roof of the

building that is reactor four, fifty metres into the sky. Awoken by the

explosion, five hundred or so residents of Pripyat made their way to a bridge

with a good view of the reactor. They

saw the light show. The core of the reactor was still firing, giving off the

biggest, most colourful fire work display ever witnessed. The five hundred or

so died within days of the radiation exposure. It’s known as the ‘Bridge of

death’ now.

The walking dead who worked at the

reactors were forbidden from discussing events with friends and family members.

For the three days it took to evacuate, they walked the streets of Pripyat.

They knew that all these friends and family had been radiated into sickness and

probably death. They also knew that all protestations would be disbelieved and

brutally suppressed, in a Soviet manner. What could the population of Pripyat

do? It was too late for protest and in any case the authorities would not

listen. It was too late for opposition to anything. The irreparable damage was

done.

Pripyat was built to house the plant

workers and their families and opened in 1970. It was a ‘show city’ in the

Soviet model; a Soviet, modernist utopia, a city of, predominantly, young

families. Kindergarten’s were so full that places were highly sought and

competed for. The next wave of nuclear scientists flocked there from all over

the Soviet territories. High wages in an exciting new city must have been very enticing. It had

a population of fifty thousand when, on the 26th of April 1986, the

mistake was made. It was a terrible mistake that had no need to happen.

Here is the official account from our

guide. An experiment had been set up by the day shift. This was to test the

electrical system which kept the all important cooling system running. The

night shift continued the experiment which ended up turning the cooling system

off. They soon found out how long a reactor will continue to run without

cooling, only seconds apparently. They even know the name of the man who

flicked the doomsday switch. What a way to make your name in history. I can’t

remember his name. It doesn’t matter. You can’t blame one man in a team that

took the most calamitous decision ever. It was a bloody fool thing to do. In

the history of human decision making it was the biggest wowzer ever.

Back to the memorial.

The liquidators were the people next in,

assigned to assess the damage and plan the clear up. One figure in the memorial,

down on one knee and with head bowed, is the picture of hopeless despair. In

reality they had no accident plan. Nothing at all. The accident was on a scale

unmatched to this day. A right mighty ball’s up that has left a scar across Europe. There are still farms in Cumbria and Wales that have restrictions on

their livestock sales. The Soviet rescue plan was cobbled together on the back

of a ciggie packet – this became increasingly clear as the utterly insane mess

of the zone was revealed to us.

Next came the kindergarten. This was the

real beginning of the trip. The building is a forgotten, Hansel and Gretel bungalow

amidst encroaching nature. The forest is taking over. The bungalow is slowly

being obscured and crowded by the trees. Our guide put her Geiger counter to

the base of a tree at the entrance. Eager to look at the reading, I stepped

from the snow onto clear ground. The reaction from our guide was insistent,

”Do not stand here. Keep to the snow. It

is serious.” Interestingly the volume on her Geiger counter was either switched

off or turned right down. Despite the high readings no clicking or alarm was

heard throughout the entire trip.

The entrance to the kindergarten had a

poster reminding the kids how to cross the road safely. The occasional, passing

Trabant car posed minimal risk, against the reactors a mile or so away.

Inside was a disturbing series of classrooms

and nap rooms. Twenty five years of dust covered all. Paperwork, school work

and toddler’s toys were strewn around the floor of each room. Phonics cards and

faded paper carpeted one room. Another contained waist high coat hooks and

lockers. The wooden lockers were self painted with Svetlana and Boris’s

personal logo’s; a teapot, a plane, a bird, a doll. Real children’s paintings

in fading primary colours, by real children who never reached adulthood. The

evacuation had been far too slow for anyone to have escaped the effects.

Leukaemia, tumours and other slow suffering were delivered to all, irrespective

of age. Children’s bunk beds occupied one room. Stripped of all blankets and

mattresses by looters long ago, the skeleton beds were in themselves shocking

and brought the tragedy over very abruptly. Children’s comfort toys lay,

discoloured by time and dust; a girl’s doll in a pink tracksuit, one eyed and

one shoe missing, face dirt blackened, with a shock of hair greyed by time.

Light through broken windows revealed and hi-lighted dust drifting in each

room. Then my camera battery died.

Other members of the party complained that

their batteries were quickly losing power. As we exchanged disappointed

mutterings our guide overheard our comments. She insisted that it was not

radiation but the cold that was affecting the cameras. This was the first

obvious lie. There would be many more. Around five minutes after we left the

building my battery came back to life, although with a much lower charge.

Others continued to have major problems with quickly dying batteries throughout

the trip. A little digging on our return brought up some interesting, if

disturbing, information. Gamma radiation depletes lithium batteries. So, not

the cold then; if cold was the problem then it would have been a problem for

the four days in Ukraine,

not just the two in the ten mile exclusion zone. What happened next was

hilarious and worrying in equal measure. We were going to visit the nuclear

plant itself, including reactor number four.

Before we began the drive we were issued

with ‘masks for safety’. We were handed a very cheap decorators dust mask. A

paper dust mask. We were to visit the very epicentre of the world’s biggest

nuclear disaster and the authorities thought a paper mask would put our minds

at rest. It obviously wasn’t for any practical reason. A paper mask, for

Christ’s sake. This was not even making an effort on their part. Spaceman, Fraggle and

I looked at each other as what just happened sank in. It was amusing and

annoying. If anything, they may well have said, “Well it’s useless where you’re

going but hey, what can we do?” Our guide, throughout the trip, repeatedly

reminded us of the seriousness of our situation. “It is very radioactive, it is

very dangerous,” both of which are true. Then they undermine it all by giving

us a mask that would struggle to keep out wood dust whilst sawing. It was

indicative of the whole thing. It is not safe, it is not under control and they

have no real idea as to what to do about it. A couple of weeks before we

arrived, heavy snow had collapsed part of the roof of the sarcophagus (tin

box!) that covers the exploded reactor. It’s got a hole in it.

We drove passed the first frozen river

I’ve ever seen to the reactors. Four were built and fired up. Two more had been

under construction but when the cock up happened construction was halted, for

obvious reasons. The Soviets had intended on building twelve reactors on the

site. The cranes and other machinery are all still there. They have no idea

what to do with it all, so there it remains. We stopped within a stone’s throw

of reactor four – the giant, radioactive blot on the bleak, winter landscape.

The reactor is intimidating. It stands

about the size of a football stadium, with the metal chimney a hundred metres

or so higher than that. We took photo’s of ourselves in front of a monumental concrete fist, very Soviet and

heroic in design, there to commemorate the workers and liquidators who died.

They really were the ‘men who saved the world’. We were all worried and wore

our silly paper masks to protect us from the radiation, unlike the construction

workers. They are building a giant dome in two pieces. The spectacularly

enormous skeleton of the first half stands on specially built tracks that will

slide the thing over the reactor, where it will be lowered to seal the site. We

were told that this new sarcophagus will last about a hundred years. It is not

even nearly ready, despite the hole in the old one. In any case it’s merely a

sticking plaster on a broken, festering limb. This will achieve little save

deferring the problem for the next generation. The fuel rods remain live and

unwell inside the building. Even the government propaganda spouted by the guide

included the fact that they have no clue as to what is going on in there. Remote

control robots die when sent inside. Ukraine has no money because

successive criminal governments have stolen it all to buy mansions and yachts

in warmer countries. They can’t afford to pay for the dome and we can’t afford

for them not to build it. Instead a whole host of countries from around the

world are footing the bill. If a slice of this isn’t being similarly filched by

the bastards in charge, I’ll eat a kebab from a stall outside Kiev central station.

All this radioactivity makes a man

hungry, famished even. It was time to eat at the Chernobyl worker’s refectory, opposite the

reactor. We filed in and had to climb into a large grey, machine to be checked

for radiation contamination. The light would either flash green for ‘go’ or red

for ‘you’re dead’. We all passed muster in the contamination stakes. The

refectory was like a school canteen, complete with hefty women in pastel blue

tabards. It was a ‘grab a tray and queue’ system. The food was also a bloody

disaster. For some reason they had pickled rice. Why would you do that? The

pickled rice contained a couple of slices of pickled pepper and a single

pickled mushroom. Sat sullenly next to this mess was a piece of meat, or

chicken, or turkey or fish. Seriously we could not decide – fish or foul or

pork or… it could have been any of them, or maybe it was grown in a nearby laboratory.

I couldn’t eat it so I took its photo instead. We never found out its provenance.

It was utterly vile. The workers at the plant have to eat this for lunch every

day. Perhaps it’s a punishment for the disaster, “Look at what you’ve done, now

eat this!” That’ll teach ‘em.

It was now mid afternoon and time for

our first peek at the ‘ghost city’ Pripyat, which is only a mile or so from the

reactors. It is silent. Nothing stirs and even birds avoid the area. The Soviet

love of concrete became immediately apparent. The whole city consists of square

slabs of grey concrete. Windows are smashed or missing. Nature has taken hold

with a vengeance. The main thoroughfare is overgrown with trees and grasses but

so is everything else. Our guide was most annoyed when a few of us strayed into

nearby buildings. “Stay out of the buildings guys, it is very dangerous.” This

why we were there, surely? We began to drift around the immediate area taking

our photo’s. Inside the buildings all had been smashed and strewn around the

floors. The Soviet army had been in after the blast to destroy anything worth

looting. Everything indoors was covered in undisturbed, grey radioactive dust.

Twenty five years worth of enforced

neglect. It was eerie and disconcerting - a dead city. It felt like something

very wrong had happened to this place, which seems obvious but it was still

very strange. We took more photo’s but didn’t stay long. The snow heavy sky was

darkening towards twilight and our guide was eager to leave. We drove back to

our luxuriant hotel. On the way we were warned not to stray outside of the

perimeter fence that night. We were told that the best that we could expect

would be arrest at gun point, the worst would be being shot by a vodka sodden

soldier.

As aforementioned, we

were billeted a mile or so from the reactor, in a corrugated iron

hut. Three English idiots were roomed together, finally. This gave us some time

to bicker and make light of the situation. Having visited the only shop in Chernobyl we had vodka to

spare. We sat watching Ukrainian TV and swapped stories until all the spare

vodka had been sensibly finished. Then, we three unsensibly blamed

each other for not buying more vodka. Even Fraggle's fantastic snoring abilities,

so loud that he’s reputedly heard occasionally in the southern hemisphere,

didn’t disturb our sleep.

Tour Day Two

Pripyat

This city is beloved by teenage computer

gamers the world over, owing to it being used as the back drop to a game called

‘Call of Duty IV’. Since our return I’ve shown the photo’s to classes of teens

and they were impressed that we’d been daft enough to visit their zombie

shooting game location. Some were amazed that it was a real place. No matter.

Here’s what happened that day.

We were led through a series of dusty,

dead buildings, each one illustrating the madness that befell them. We wandered

through the residential areas, seemingly endless blocks of flats. They were all

tiny box rooms, some containing sofas and other ephemera - snapshots of real lives. The rooms were so small, yet

designed to accommodate families in the ideal communist future. Chairs and

cookers, cock-eyed and awaiting their former residents, littered the interiors.

Six floors up a lone tree grew from the cracked floor of a balcony, a lonely chair

awaiting an occupant sat beside it. A concert hall with seats ripped out,

complete with stage and grand piano left to rot. The high school with classrooms

filled with dusty, lives not led.

Blackboards still contained lessons

forgotten, now irrelevant. The staffroom with registers with discernable names

and course marks, all now redundant, resonated with me. I recognised it all

from my own life as a teacher.

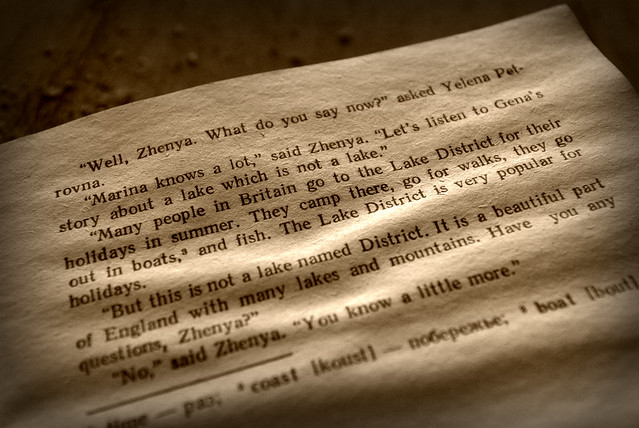

There was a language classroom with text books

opened at the day’s lesson. It was in English, “Russian must not be spoken in

English lessons.” The science rooms were littered with test tubes and texts

informing the kids about the mechanics of chemistry. The cafeteria still had

plates and pop bottles where they were left at the end of the ‘final supper’.

These people didn’t evacuate – they fled. Each room drove home the enormity of

the disaster on individual lives. It all began to segue into one depressing

impression of helplessness. It was awful and fascinating, lives innocently

half-lived. The street lights were adorned with peeling posters extolling the

virtues of a bright, Leninist future. We found a large bust of the man in a

public toilet, spattered with white paint.

A small fun fair had been built with a

Ferris wheel and bumper cars and swings. It was to be opened on the May-day

celebrations of 1986. It was never opened. The bumper cars never bumped, the

swings never swung, the ‘big wheel’ never turned and all the children are dead.

A child’s shoe lay in the snow next to the Ferris wheel.

Creepy graffiti was sprayed

in odd places. A painted interloper crept up the fire escape to the theatre’s

back door; the words in English daubed, ‘Dead Don’t Cry’ on an administrative

building, a girl with wild, blonde hair bouncing on a space hopper, grinning as

if in manic defiance to events. A swimming pool with no water, looked down upon

by a clock stuck at five past six, on it went, on and on. By the end of it all

I was exhausted by the grim reality. I was glad to leave.

That night we headed back to the cellar

bar in Kiev. We

drank cider with vodka chasers and talked nonsense. I fell into talking to a

government economist with impeccable English. He was glad to talk to an

outsider, as this enabled him to unload his views and opinions in a way he

couldn’t with friends. He told me that Chernobyl

is a national embarrassment and is consequently never mentioned; not between

friends, never at work and never in school. The people of Ukraine are

shielded by censorship from the events in 1986. I asked him about their ex-president,

Julia Tymoshenko. On being forced from office she was arrested and accused of

dodgy dealing with the Russians. She was sentenced to eight years in prison.

She has been beaten and denied medical treatment. She is now being charged with

murder on what I believed to be trumped up charges. When I told him how the

English press treated her as a prisoner of conscience, he was aghast. He

beckoned me to lean in closer. “She is in the right place. She is a criminal.

You must understand, to gain power in Ukraine you must be a gangster.

Elections are a mere formality, for appearances only, a fraud.” Was this just

his opinion or was it the consensus in Ukraine? “I’ll show you,” he called

to different people in the bar to elicit their response to the Tymoshenko

question. Each one gave the same answer in English. “I don’t give a shit about

Tymoshenko, she is criminal.” He turned back to me and nodded, “You see now?

When our current president leaves office we will put him in prison also!” He

threw his head back and began to laugh heartily.

Good night Kiev,

goodbye Ukraine.

Tin Dog.

18th April 2013

Copyright 2013 Fragglehunter (photos) Tin Dog (words)

Do not reproduce in whole or part without permission of the Copyright holders.

Fantastic report. This brought back a few memories, as well as offering some new perspectives. I like the way you've started and finished in Kiev, giving a slightly broader view of your experiences and perceptions of the place.

ReplyDeleteThink I might have to go back in Winter now, these snow shots are really selling it...

I'm so glad I did it in winter at its bleakest, the snow and ice was hard going, but we didn't feel the cold . The only sound we heard was the breaking of the snow and ice beneath our feet. The snow muffled any sounds, the silence was deafening at times.

DeleteThis is amazing.. so amazing.. And haunting.

ReplyDeleteI've just returned from my third trip to Kiev this year. I actually love that city. a lot has changed in 9 months, they really want some democracy. without all the fraud that has been happening the last decade.

ReplyDeleteYou've written a very interesting article about chernobyl, and it makes me want to visit Chernobyl myself. The only thing that is still holding me back is the price sadly enough.

Do you happen to know if I could find a day tour for less than 100 euros?

And where should I look for such a tour?

thanks for the feedback, I am aware that you can get in with the help of locals who act as unofficial guides (remembering it is under armed guard - but the place is so vast). I'm not sure who should ask, but clues are out there on places like National Geographic.

ReplyDeleteQuality read! It made me laugh out loud in parts and also addresses the seriousness of the whole situation. 10/10

ReplyDeletehe's a wordy guy - thank you

Delete